Guide to Cannabis Types: Indica, Sativa, Hybrids, and Autoflowering

The Origins of Cannabis

Cannabis is one of the oldest plants known to humanity, with origins in Central Asia over 5,000 years ago. Early civilizations used it for fibers, textiles, medicine, and spiritual practices.

Over the millennia, cannabis spread across continents, naturally adapting to different environments. In the mountains of the Hindu Kush (Afghanistan, Pakistan), it developed Indica characteristics: short stature, compact structure, and rapid flowering. In equatorial regions (Thailand, Colombia, Kenya), it evolved as Sativa: tall, long-flowering, and adapted to warm climates. In the Siberian steppes, it became Ruderalis: small, hardy, and capable of automatic flowering.

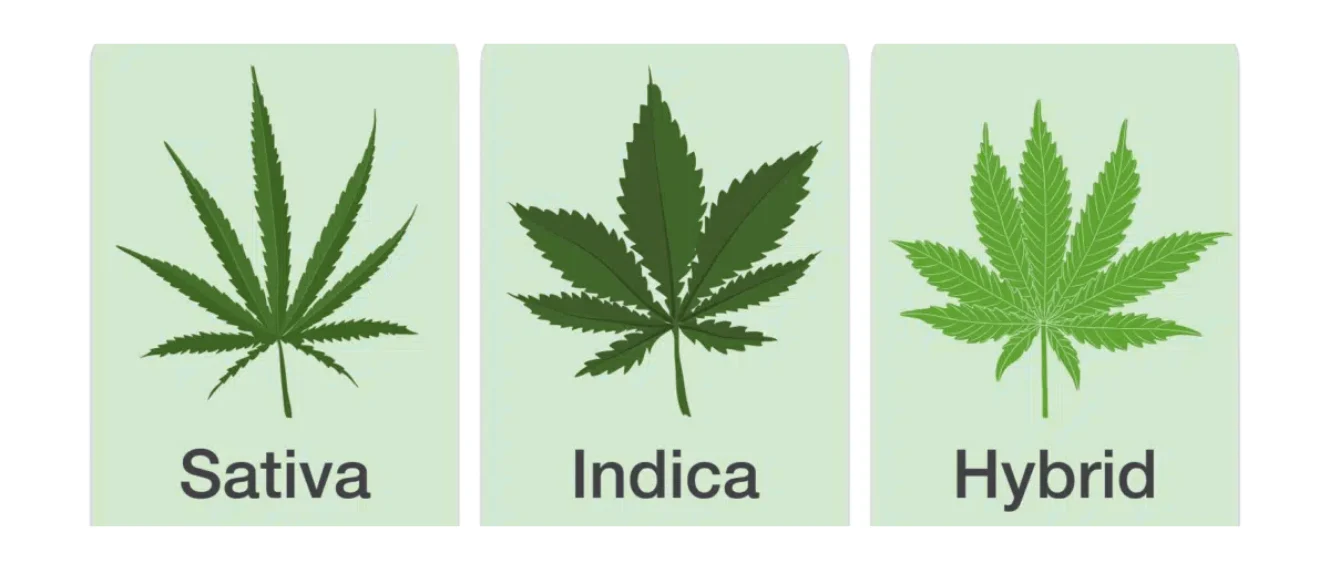

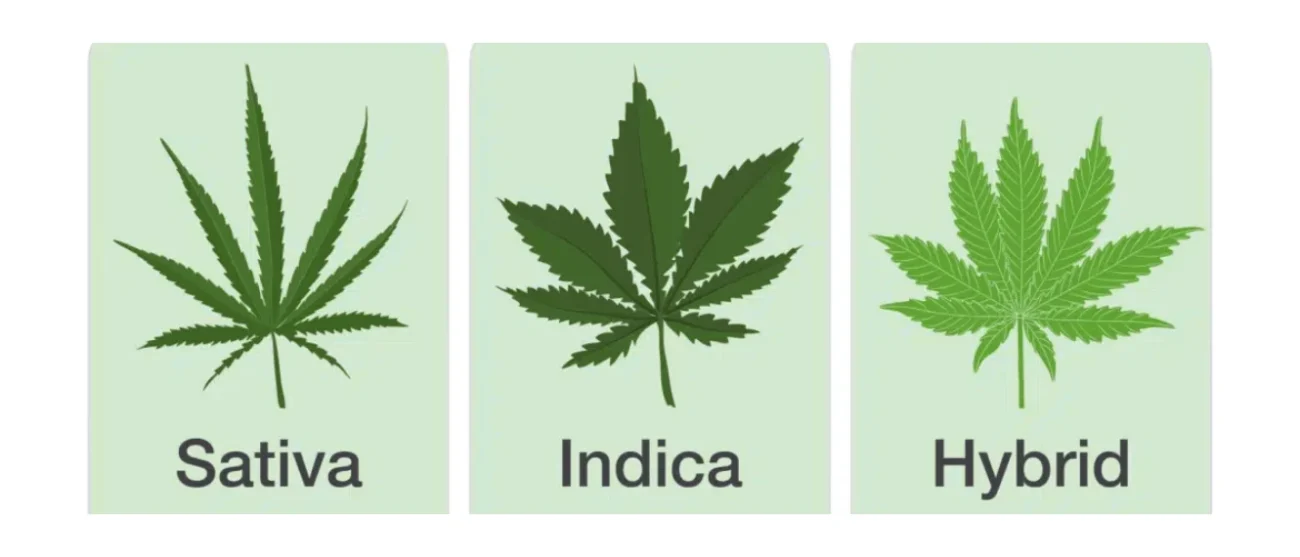

Introduction: Understanding Cannabis Varieties

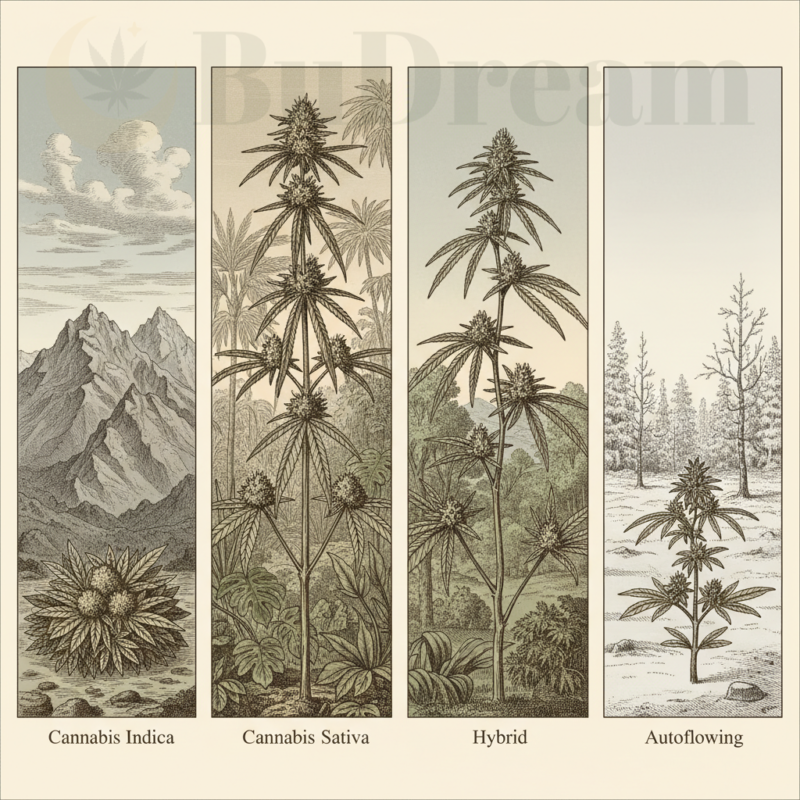

There are several types of cannabis, each with unique botanical characteristics that developed in response to their environments of origin. Understanding these differences is essential for recognizing the biodiversity of this plant.

The main categories are Indica (compact structure, short cycle), Sativa (tall structure, long cycle), Hybrids (a combination of traits), and Autoflowering varieties (life cycle independent of light).

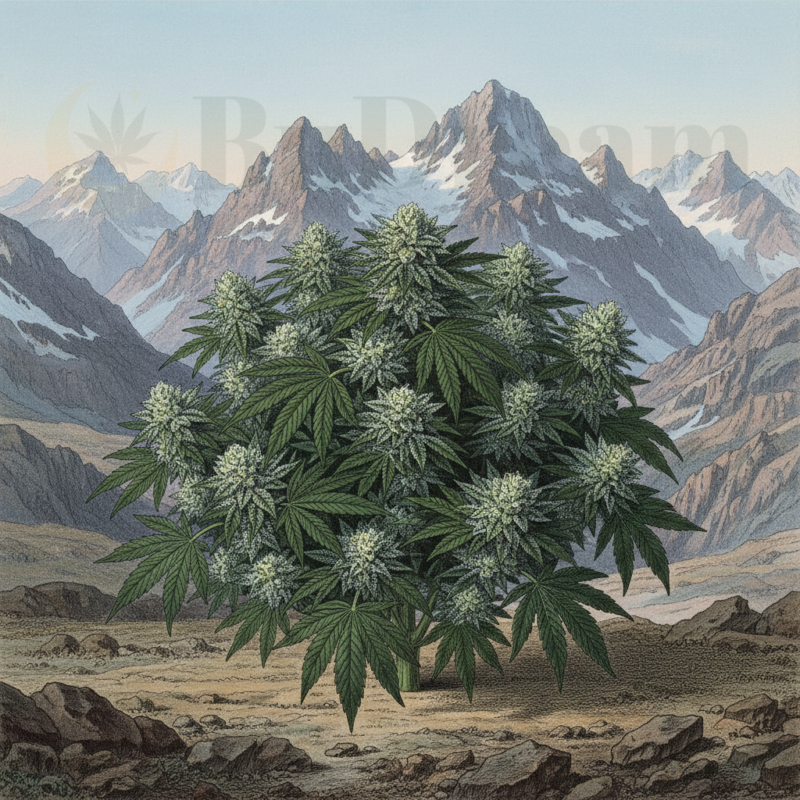

Cannabis Indica: Botanical Characteristics

Indica plants have a compact structure, appearing short and dense with a bushy form. Leaves are broad, short, and generally dark green, with very tight internodal spacing. The flowering period is relatively short. These plants originate from the mountainous regions of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Kashmir.

Indica evolved in mountain environments characterized by harsh winters, short growing seasons, and fewer hours of sunlight. These conditions led to the development of a compact structure to withstand wind, broad leaves to maximize light capture, a rapid maturation cycle to complete reproduction before winter, and high resistance to cold and humidity.

Indica flowers are dense and compact, with a solid, heavy structure. They produce abundant resin due to a high concentration of trichomes, the glands that contain cannabinoids and terpenes. This trait evolved as a defensive mechanism against cold mountain temperatures.

From a climatic perspective, Indica thrives in temperate and cool environments. It is naturally suited to regions with short summers and early winters due to its ability to complete its life cycle quickly. Its resistance to mold is higher than other varieties, inherited from adaptation to mountain nighttime humidity.

Cannabis Sativa: The Equatorial Giant

Sativa plants are very tall and slender, with predominantly vertical growth. Leaves are thin and elongated, with narrow fingers and a light green color. Internodes are widely spaced, creating an open and airy structure. The flowering period is notably long. These plants originate from equatorial regions such as Colombia, Thailand, Mexico, and Central Africa.

Sativa evolved in hot and humid climates with growing seasons that last nearly all year. Thin leaves promote transpiration and heat dissipation. The tall, open structure improves air circulation in humid environments, reducing the risk of fungal diseases. The considerable height is a response to competition for light in equatorial forests.

A characteristic behavior of Sativa is “stretch,” the significant elongation that occurs during the first weeks of flowering. While Indica plants largely stop vertical growth once flowering begins, Sativas can double or even triple in height during this phase.

Sativa flowers are longer and less dense than those of Indica, with a more open structure. This morphology reduces the risk of internal mold and promotes airflow. Flowers develop along the entire length of the branches, forming elongated structures often referred to as foxtailing.

Sativa requires warm climates with long summers and thrives even at high temperatures. However, its late flowering period can make it vulnerable to seasonal humidity. Heat resistance is excellent, while mold resistance depends heavily on specific genetics and local adaptation.

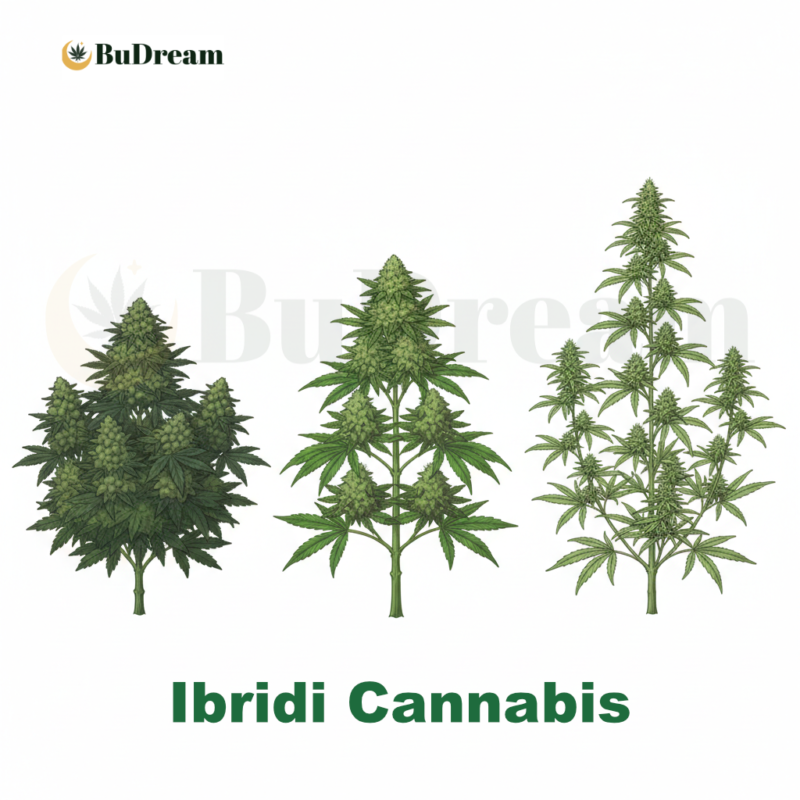

Hybrids: Combined Genetics

Hybrids are the result of crossing Indica and Sativa genetics. Through decades of selective breeding, varieties have been created that combine traits from both parent types. Hybrids can be classified as Indica-dominant (60–80% Indica), Sativa-dominant (60–80% Sativa), or balanced (approximately 50/50).

Indica-dominant hybrids retain a relatively compact structure and a shorter flowering period while incorporating Sativa elements such as greater aromatic variability or a slightly more open flower structure. Final height remains manageable, and maturation time is moderate.

Sativa-dominant hybrids preserve the vertical growth energy and yield potential of Sativa but with reduced height and shorter flowering periods compared to pure Sativas. Stretch during flowering is present but controlled, making these plants more versatile.

Balanced hybrids aim to offer equal characteristics of both parent types. They display medium height, intermediate flowering times, and a structure that combines Indica density with Sativa internodal spacing. These hybrids often show high adaptability to diverse environmental conditions.

Most modern commercial varieties are technically stabilized hybrids. Through successive generations of selection (F2, F3, F4, and beyond), desired traits are genetically fixed, producing uniform and predictable plants. Even strains marketed as “pure Indica” or “pure Sativa” are often highly stabilized hybrids expressing predominantly one set of characteristics.

Hybridization has enabled the creation of varieties suited to specific climates, overcoming the limitations of pure genetics. Modern hybrids represent decades of selective breeding and the continuous evolution of the species under human influence.

Autoflowering Cannabis: Ruderalis Genetics

Autoflowering cannabis represents a genetically distinct category based on the incorporation of Cannabis Ruderalis. Ruderalis is a subspecies native to Siberian regions and Eastern Europe, where it evolved in areas with extremely short summers and harsh climatic conditions.

The defining characteristic of Ruderalis is automatic flowering. Unlike Indica and Sativa, which initiate flowering in response to changes in photoperiod, Ruderalis flowers automatically based on plant age, typically three to four weeks after germination, regardless of light exposure.

Pure Ruderalis plants are small, low-yielding, and contain minimal cannabinoid levels, making them of little interest on their own. However, the autoflowering gene is revolutionary when combined with other varieties.

In the early 2000s, breeders began crossing Ruderalis with potent Indica and Sativa genetics to transfer the autoflowering trait while retaining desirable qualities. Early generations were small and low-yielding, but quality improved dramatically over successive generations.

Modern autoflowering varieties typically consist of 60–70% Indica or Sativa genetics and 30–40% Ruderalis. This balance preserves the autoflowering gene without excessively sacrificing quality or yield.

Distinctive features of autoflowers include an extremely rapid life cycle, compact size, and complete independence from photoperiod. They can receive any light cycle without affecting the onset or progression of flowering.

Ruderalis heritage grants autoflowers exceptional resistance to cold, environmental stress, and disease. Autoflowers tolerate low night temperatures that would severely damage photoperiod varieties.

Botanically, autoflowers represent a clear example of how extreme evolutionary traits can be transferred through controlled hybridization, creating new combinations of characteristics not typically found in nature.

Comparison of Types: Botanical Differences

The four cannabis categories show significant morphological, physiological, and life-cycle differences rooted in their evolutionary adaptations.

In terms of height, Indica remains the shortest, Sativa is the tallest, hybrids vary at intermediate heights, and autoflowers are the most compact.

Total life cycle length varies greatly. Indica completes its cycle relatively quickly, Sativa requires much longer periods, hybrids fall in between, and autoflowers are the fastest from seed to maturity.

Leaf morphology is distinctive for each type. Indica has broad leaves, Sativa has thin elongated leaves, hybrids show intermediate forms, and autoflowers tend to have smaller leaves depending on dominant genetics.

Internodal spacing reflects environmental adaptation. Indica has very short internodes, Sativa has widely spaced internodes, hybrids are intermediate, and autoflowers generally have relatively short internodes.

Flowering behavior also differs. Indica largely stops vertical growth once flowering begins, Sativa continues vigorous growth during early flowering, hybrids show controlled stretch, and autoflowers grow continuously but remain limited in size.

Environmental resistance varies by origin. Indica excels in cold and humidity resistance, Sativa excels in heat resistance, hybrids often combine multiple resistances, and autoflowers show the highest overall resilience due to Ruderalis heritage.

Flower structure differs as well. Indica produces dense and compact flowers, Sativa produces elongated and airy flowers, hybrids are intermediate, and autoflowers tend toward compact flowers of smaller size.

Applications and Contexts

Each cannabis type’s botanical traits make it suitable for specific contexts, considering space availability, climate, and research focus.

Indica’s compact structure and short cycle make it relevant for environments with limited space or short growing seasons. Its cold resistance makes it valuable for studies in temperate climates.

Sativa’s imposing structure and long cycle are relevant to warm climates with extended seasons. Its morphology is of interest for research on plant competition and equatorial adaptation, requiring ample vertical space.

Hybrids provide insight into genetic combination and adaptability, representing the species’ evolution under artificial selection.

Autoflowers are especially relevant to evolutionary genetics, demonstrating the integration of extreme adaptive traits. Their speed, compactness, and resilience make them suitable for studies under time or space constraints.

Educationally and botanically, each type offers unique opportunities to study evolutionary adaptation, phenotypic plasticity, and selective pressure over time.

Biodiversity and Conservation

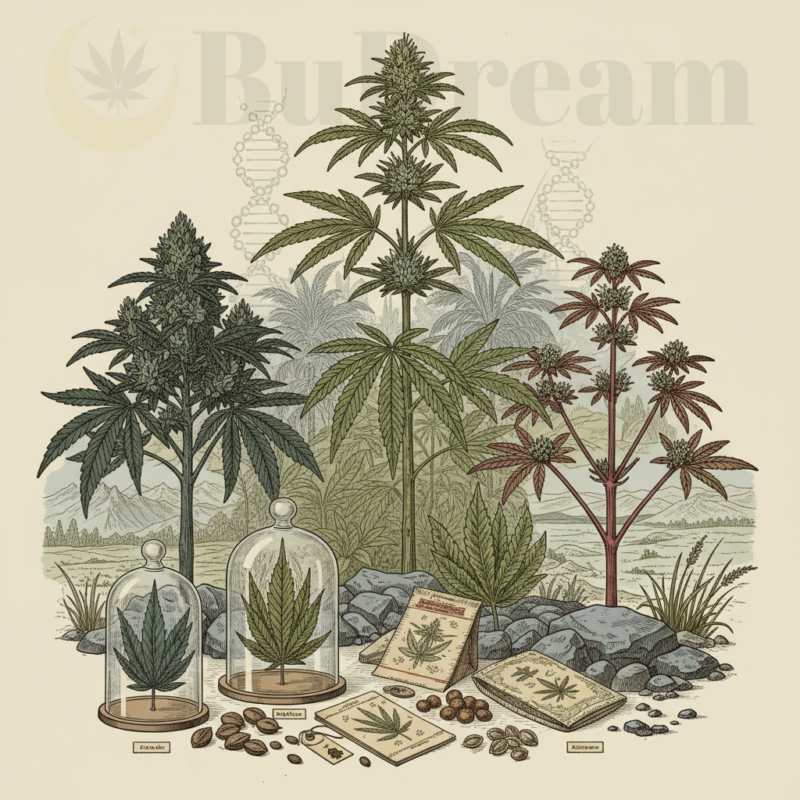

The diversity among Indica, Sativa, hybrids, and autoflowering varieties represents a significant reservoir of biodiversity. Original landrace varieties, pure non-hybridized genetics from native regions, are increasingly rare and constitute valuable genetic material for research and conservation.

Native populations face growing environmental pressure due to climate change and habitat loss. Preserving these original genetics is crucial for maintaining species diversity.

While modern hybrids offer many advantages, they have also contributed to genetic erosion, with many commercial varieties deriving from a limited gene pool. Seed banks and botanical collections play an important role in preserving historical genetic diversity.

From a scientific perspective, each type represents a natural or artificial experiment in adaptation and selection, offering valuable insight into genetics, evolution, and plant biology.

IMPORTANT LEGAL NOTICE

Cannabis laws vary widely between countries. In many jurisdictions, the cultivation, possession, or use of cannabis may be illegal or subject to strict regulation, regardless of quantity, purpose, or plant characteristics.

This text is intended exclusively for educational, scientific, historical, and botanical purposes. It does not provide instructions for cultivation, use, or distribution, nor does it encourage or promote any activity that may violate local laws.

Readers are solely responsible for knowing and complying with the laws and regulations applicable in their country or region. The author and distributors assume no responsibility for any misuse of the information contained herein.

This guide is provided strictly as academic and scientific reference material.

Pest control

Pest control Fertilizer

Fertilizer LED lamp

LED lamp Fans and extractors

Fans and extractors Pots

Pots